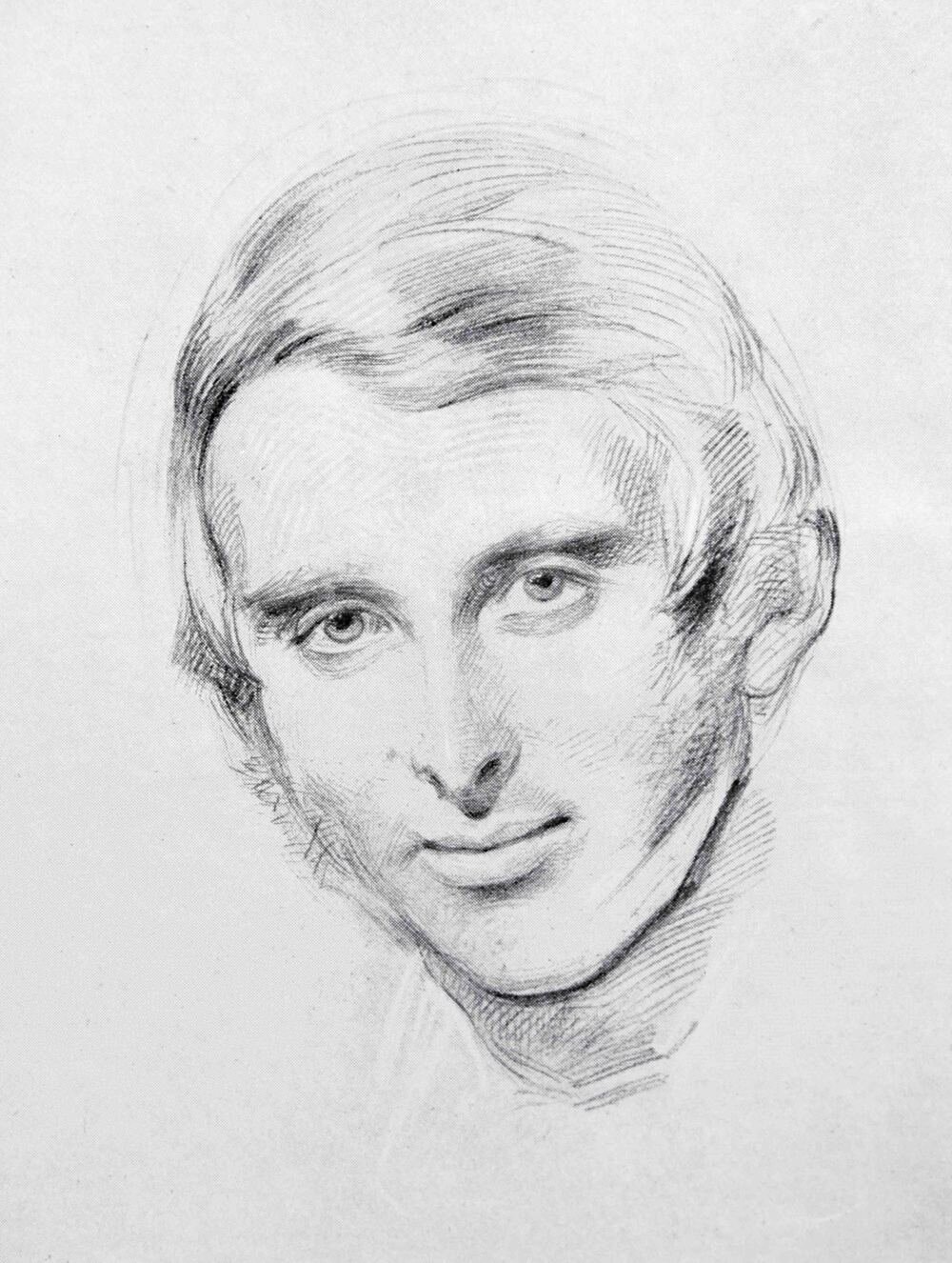

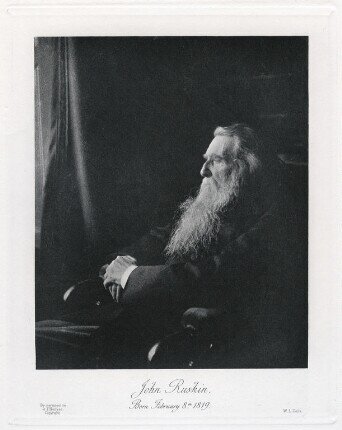

Art and social critic John Ruskin was born on February 8, 1819 in London and died at Brantwood in the Lake District on January 20, 1900.

The only child of a well-to-do Scottish couple, Ruskin grew up in a cultured household in which both his father’s artistic interests and his mother’s fervent Evangelical faith were central themes. Ruskin pere’s profitable sherry business enabled the family to make annual pilgrimages to Italy, France and the Alps where, from a young age, Ruskin’s aesthetic appetites were nourished on a broad exposure to European architecture and painting, and the watercolors and drawings of Turner his father collected.

An accomplished draftsman himself, even as a child, Ruskin recorded a lifetime of impressions in a vast output of drawings and watercolors of architecture, plant life, atmospheric effects, geological formations and other natural phenomena.

His art critical acumen was also on early display. He had published three essays – one “an inquiry into the color of the Rhine,” a spirited defense of Turner for Blackwood’s, and an article on the “poetry of architecture” – before he was eighteen. While at Oxford, he won the Newdigate Prize for poetry in 1839.

At age 24, Ruskin published the first volume of the work that would make him famous: Modern Painters, a seminal defense of Turner that, as novelist Charlotte Bronte later wrote, taught a generation how to see.

Between the years 1843 and 1860, Ruskin wrote, in addition to installments of Modern Painters, The Seven Lamps of Architecture, and The Stones of Venice – books that influenced 19th and 20th century aesthetic trends from the Pre-Raphaelites, plein-art landscape painting, and the Arts and Crafts movement to Frank Lloyd Wright. With his championing of early Italian “primitives,” Gothic architecture, “truth” in the depiction of nature and “organic” architecture, Ruskin, as one art critic writes, “shaped a whole sensibility.”

These years also witnessed Ruskin’s ill-fated marriage to Effie Gray, who later married the painter, and Ruskin protégé, John Everett Millais in 1854.

While Ruskin never stopped writing and lecturing about art, by 1860, his focus had shifted to social criticism. Increasingly tormented by the poverty and squalor he saw around him in Victorian Britain, Ruskin began to challenge, in vivid, passionate language, the political, economic, and ethical assumptions undergirding industrial society, and to propose a radical link between art and social reform. In works from Unto This Last (1860) to Fors Clavigera (1871-1884), his series of ninety-six letters to the workers of Great Britain, Ruskin laid out a visionary program that would increasingly bewilder and finally alienate much of his conventional audience. Ruskin’s ideas, however, would go on to animate trade unionists and labor leaders in Britain and America, leaders of the growing Arts and Crafts movement, modernist designers and prove life-changing for figures as diverse as Marcel Proust, William Morris, Leo Tolstoy, Bernard Shaw and Mahatma Gandhi.

Acting on his own critique, Ruskin taught drawing free of charge at the Working Men’s College in London, enlisted his students in building projects in slums, endowed schools, libraries, and museums in working-class areas, supported a small retinue of artists and founded a crafts-based community, the St. George Guild, into which he poured his considerable fortune.

In the 1870s and ‘80s, “Ruskin societies” sprang up in Britain and America to advance the master’s vision of the unity of life and art. The Ruskin Art Club, founded in Los Angeles in 1888, is a living example of that impulse.

For Ruskin himself, however, these were troubled years. By the 1880s, Ruskin’s life alternated between a series of mental breakdowns and lonely, desperate attempts to influence what he perceived as an increasingly indifferent public. That struggle culminated in the hauntingly beautiful (and unfinished) memoir, Praeterita, and, in 1889, with a mental collapse from which he never recovered.

John Ruskin died at his Brantwood estate in 1900.

FOR FURTHER READING, CONSULT:

John D. Rosenberg, “The Genius of John Ruskin: Selections From His Writings” (1963), reprint 1998, University of Virginia Press ISBN 0813917891

John D. Rosenberg, “The Darkening Glass: A Portrait of Ruskin’s Genius,” (1961), reprint 1986, Columbia University Press ISBN 0231063873.

Daisy Dunn, “Was Ruskin the most important man of the last 200 years?” (2019)

Scott Reyburn, “Why John Ruskin, Born 200 Years Ago, Is Having a Comeback” (2019)